Rediscovering Walter Sickert

London's Tate Britain and Paris' Petit Palais have collaborated to produce a wonderful retrospective exhibition of the art of Walter Sickert (1860-1942). The show is both beautiful and fascinating.

As a young artist, Sickert worked briefly in the studio of James A.M. Whistler, from whom he learned to make etchings. In 1883, he first met Edgar Degas, when he traveled to Paris to deliver Whistler's Portrait of the Artist's Mother to the Salon of French Artists. Sickert's friendship with Degas would outlast his relationship with Whistler, but both older artists would be important influences on his work.

During the 1880s, Sickert painted urban scenes and landscapes that closely followed Whistler. Unlike Whistler and Degas, Sickert painted from preparatory drawings that he squared up to transfer images to canvas. Sickert's work presents a paradox. His two major influences were great experimental painters who worked directly and visually, without preparatory drawings. And Sickert's finished paintings resemble those of Whistler and Degas, with freely applied brushstrokes and imprecise contours. Yet for Sickert, these were the product of systematic use of preparatory drawings, and underdrawing on his canvases. Sickert thus appears as a curious example of a conceptual painter mimicking the work of experimentalists - using a conceptual process to make paintings that appear direct and experimental.

Sickert loved music halls, the theatre, and the circus, and in his studio he converted sketches he made during performances into paintings. These atmospheric works did not find receptive collectors, and during the 1890s he tried to earn a living as a portraitist. Yet this attempt was unsuccessful, as the informality of his images did not satisfy his conventional patrons.

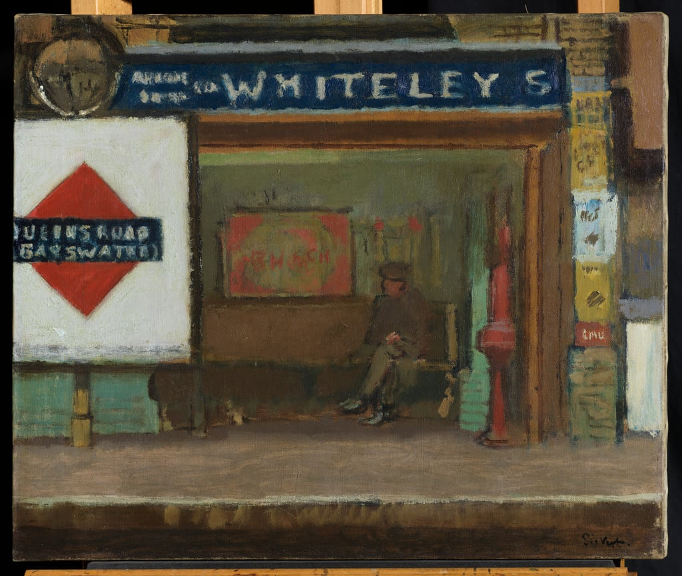

Abandoning portraiture, Sickert came under the influence of another great experimental master, as his series of views of churches in Dieppe and Venice paid homage to Monet's series paintings, which Sickert saw in Paris, in the gallery of Durand-Ruel, who also represented Sickert. As he devoted himself to urban scenes, often in Paris and London, an interesting indicator of his conceptual nature sometimes appears in the legible lettering of advertisements, shop signs, and subway stations.

For a decade after 1900, Sickert painted scandalous images of earthy nudes, in shabby bedrooms redolent of poverty and the working class. The informal and often awkward poses of his models were influenced by Degas, and in turn became influences on Lucian Freud and other younger English realist painters.

After 1915, Sickert gave up drawing, and developed a technique of painting based on transposing photographs onto canvas. From the mid-1920s, he routinely painted by projecting photographs from glass plates onto canvases with the use of a camera lucida. Not surprisingly, these late paintings were extremely controversial; today they can be seen as anticipations of such conceptual painters as Gerhard Richter and Andy Warhol.

The charm of Sickert's art lies in the fact that, like Whistler and Degas, he was a painter of the small scale. Even on the occasions when he chose a monumental motif, like St. Mark's Basilica in Venice, he did not make it distant and imposing, but reduced it in a close view to a human scale. Virginia Woolf loved Sickert's art, and it is not difficult to see why, because his painting, like her writing, was always about intimate views of incidents, or casual portraits in which individual sitters momentarily revealed their personalities. Sickert's descriptive brushstrokes parallel Woolf's informal prose, and his carefully framed views parallel Woolf's moments of being, when a glimpse of a street corner or of an old friend conveys a sense of an inner life beyond surface appearances.

Sickert's art never gained the status of that of Whistler or Degas, perhaps because it was too derivative of those masters. But he was an important link between those great experimental painters and the art of Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach, and their fellow members of the School of London. With this excellent exhibition, it is possible that his influence will be passed on to yet another generation of experimental painters.